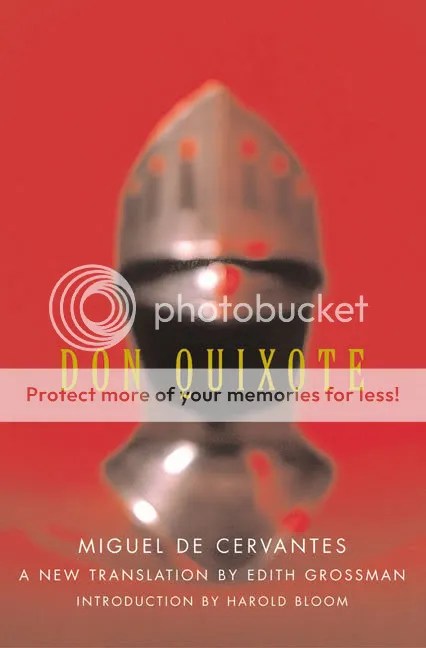

Booklog: Don Quixote

February 17, 2007 Don Quixote

Don Quixote

Miguel de Cervantes

(translated by Edith Grossman)

Read: 2.13.07

Rating: Extraordinary

Typically, when composing these “booklogs” I strive to formulate some sort of over-arching critical opinion, hoping to name and evaluate the text’s main themes or ideas. This isn’t necessarily the best way to evaluate a book, but it’s how I’ve been doing it all my life, and it’s something I enjoy immensely. But when it comes to works like The Odyssey or Don Quixote there is little point in attempting such a project. The proper response to masterpieces like these, which have been rightfully praised for centuries, is one of profound awe and surpassing delight. All that I can do is add my voice to the chorus, and explain a few aspects of the text I found to be particularly wonderful.

Capacity to surprise. Often when approaching a classic we have events and passages from the book already present in our minds. We know that Achilles will kill Hector, that Aeneas will visit Hades before founding Rome, that Dante will emerge from the Inferno. I knew Don Quixote would attack the windmills and generally find new ways to make a fool of himself, but I had no idea that this famous scene would occur in chapter eight, a mere forty pages from the book’s opening words, and that Cervantes’ description of the Don’s attack is no more than one sentence. Here’s what happens:

First, Don Quixote is riding through the country side with Sancho Panza:

As they were talking, they saw thirty or forty of the windmills found in that countryside, and as soon as Don Quixote caught sight of them, he said to his squire:

“Good fortune is guiding our affairs better than we could have desired, for there you see, friend Sancho Panza, thirty or more enormous giants with whom I intend to do battle and whose lives I intend to take, and with the spoils we shall begin to grow rich, for this is righteous warfare, and it is a great service to God to remove so evil a breed from the face of the earth.”

“What giants?” said Sancho Panza.

And so on — the knight and his squire discuss the giants/windmills for about twenty seconds, then Don Quixote announces his intentions and charges:

And saying this, and commending himself with all his heart to his lady Dulcinea, asking that she come to his aid at this critical moment, and well-protected by his shield, with his lance in its socket, he charged at Rocinante’s full gallop and attacked the first mill he came to; and as he thrust his lance into the sail, the wind moved it with so much force that it broke the lance into pieces and picked up the horse and the knight, who then dropped to the ground and were very badly battered.

That’s it — one sentence of description. The action is economical and perfect in its brevity. All of the book is like this: actions are described quickly and efficiently, so that Cervantes can get to the heart of what’s hysterical and heartbreaking about the Don’s actions. The greatness of the text comes from the discussions and dialogs: Don Quixote’s insistence that the world around him in enchanted, Sancho’s simplicity and humor, etc.

Another surprising aspect of the novel is how quickly it reads, and how much forward momentum the chapters have. Cervantes is a master at straddling chapter breaks, and the short descriptions that precede each chapter (e.g. “Regarding the good fortune of the valorous Don Quixote in the fearful and never imagined adventure of the windmills, along with other events worthy of joyful remembrance”) are sufficiently appealing — it’s hard to put the book down after you get going. Don Quixote does not in any way suffer from the staleness and feeling of drudgery than we often associate with the reading of classic texts. It’s also as amusing and hilarious as a book can possibly be.

Meta-fiction. Another aspect of Don Quixote that impressed me was the playful, meta-fictional quality of the text. Cervantes’ novel displays a mastery of many qualities we are used to associating with modern fiction: “mini-novels” within the novel, a slippery, shadowy narrator/translator, a ironic tone of knowingness, and, most importantly, a sense of the novel as a text that is read and interpreted by the public. The text contains two “interpolated novels,” one of which, The Man Who Was Recklessly Curious, is over forty pages long — quite enough to be considered a “novella” by modern standards. The story of the text’s origin, as recorded by the book’s narrator (who is more-or-less Cervantes — also meta-licious) is very curious: the narrator claims to have found a text, written by a Moor named Cide Hamete Benengeli, which he then had translated. This explanation comes hundreds of pages into the text, and the narrator breaks in from time to time to praise Cide Hamete Benengeli, noting that, even though he was a Moor, he was certainly a good reporter and writer. The text and its narrative operate on multiple layers, which enhances what I consider to be the main theme of the book: Don Quixote’s distinctly literary form of madness, and the reaction to it of those around him — both those who participate in his adventures and those who have heard or read about them.

Don Quixote’s madness. The back cover of my HarperCollins paperback tome has a glorious array of fine quotations praising Don Quixote. This is hardly unusual, but these snippets come not from contemporary reviewers, but from Lionel Trilling, Nabokov, and Thomas Mann, among others. The best and most helpful praise comes from Carlos Fuentes, who rightly says:

Don Quixote is the first modern novel, perhaps the most eternal novel ever written and certainly the fountainhead of European and American fiction: here we have Gogol and Dostoevsky, Dickens and Nabokov, Borges and Bellow, Sterne and Diderot in their generic nakedness, once more taking to the road with the gentleman and the squire, believing the world is what we read and discovering that the world read us.

Whew — this is most fine. The final part of this quote, “believing the world is what we read and discovering that the world read us” perfectly encapsulates what I loved most about Don Quixote: even though the man is perfectly mad, he is only insane in the fact that he considers himself a knight errant. The book is full of insightful, learned lectures that come from the mouth of the Don, including one polemic on the nature of good government that is a perfect summary of non-Machiavellian Renaissance political theory. Sancho and the book’s other characters never cease to be amazed by Don Quixote’s mixture of sanity and insanity. The only thing wrong with Don’s head is that he believes that there is still a place in the world for a knight errant, and that the fantastical things he reads in his books of chivalry actually occurred. Of course, they didn’t — but can he be faulted for wishing that they did? I know I spent most of my childhood wishing I was a knight, with a famous sword and maiden to rescue.

Whenever Don Quixote is met with disbelief, and is told that knight errants never existed and the tales he has been reading are pure fiction, he responds by arguing that such knights must have existed, because the descriptions of their quests are so memorable and full of detail (namely, they are well-written), and — this is what really kills me — knight errantry is the most perfect and virtuous occupation a man could ever wish for: a life of virtue and adventure, righting wrongs and protecting the poor and the unfortunate. The Don is certainly right in pointing out that the world would be (or is) a better place because of knight errants. His madness is a lovely madness.

The second half of Fuentes’ quote, “discovering that the world reads us,” references the text’s Second Part, which Cervantes composed ten years after the First Part was published. As the story goes, Don Quixote has taken some time off, and by the time he takes his “third sally” in Part Two, the learned world is aware of his escapades, for they have read about them in Part One. As Don Quixote and Sancho sally into new situations, they often encounter a person or group who knows about them and therefore hope to join in their adventures. In particular, the two meet a Duke and Duchess who are big fans of the knight and his squire, and take great pleasure in playing along and tricking the two for their own amusement. Don Quixote and Sancho Panza become “Don Quixote” and “Sancho Panza,” the ingeniously mad knight errant and comical squire of the story, as their “true” and “fictional” selves become one. It will boggle your mind, in all the right ways.

Translation. I’d like to close by strongly recommending this recent translation by Edith Grossman, published in 2003 by HarperCollins. Obviously, I haven’t read any other translations, but it’s hard for me to imagine one being better. It reads quickly, the style is the perfect mixture of high and highly amusing, and the footnotes are brief, very informative, and in the right place (that is, at the bottom, and not in the back). I was particularly impressed by Grossman’s ability to translate almost all of Sancho Panza’s proverbs and amusing misuses of words into English. Sancho is a treasure-trove of proverbs — there are hundreds of them in the text, and nearly all of them are so well-ingrained into our Western consciousness as to have modern English equivalents. Whenever the wordplay cannot be adequately translated into English, Grossman explains it in a footnote.

Don Quixote is as good as literature gets. If you haven’t read it, and aren’t planning to, I hope you’ll change your mind. I was once in your position, and I’m glad I came around. You’re punishing yourself if you go to the grave without having read Cervantes’ masterpiece.

“Here,” said Don Quixote when he saw it, “we can, brother Sancho Panza, plunge our hands all the way up to the elbows into this thing they call adventures.”

I’ve been planning on reading the Grossman translation, so I’m glad you liked it so much. We have another translation at home, but I think I’ll pay the money to get hers.

The meta-fictional and high-ironic bits (especially in part two) really threw me. It was hard to believe I was reading a contemporary of Shakespeare and not a twentieth century author. Like you say, it boggles the mind in all the right ways.

What a terrific review! I read an earlier translation, and if pushed to pick one, I would have to call Don Quixote my favorite book. I have the Grossman edition on the shelf- I’m saving it for some long summer days.

I’ll definitely have to look into this, although, admittedly, I find footnotes to be very distracting. I’ve always wanted to read this book, but I agonize over which translations to get. In my post on reading “DQ,” the author I quoted had conceded that he probably wasn’t enjoying the book because of the “stodgy” translation (I don’t remember which translation he’d been reading, though). In any case, I’ll definitely look further into this translation, as well as others.

[…] is a combination of the Iliad (wars) and the Odyssey (a man). As you know, Virgil succeeded wildly. Just as with Don Quixote, typical critical conceptions are out of order, and what will follow is a celebration of some of my […]

[…] Ted 11:50 pm Since I will not be fully participating in the reading of Don Quixote, having just finished it a few months back, I thought it would be fun to read and report on Vladimir Nabokov’s […]

[…] you’d like to see how to review a great book on a literature blog read Myrtias (I do). If you would like to read a rambling non-review of a great book that struggles not to […]

bernard hill actor

Man i just love your blog, keep the cool posts comin..

I have always been a fan of the character, Don Quixote. And for some reason, every time I see his name used in reference to a bad move or strategy, I always cringe. You see, for me Don Quixote is a man of action. Despite his mistakes, his intent is good and he dares to move on his ideas where most others rest.

For this reason, I started a blog and business concept based on him. My blog is called “Quixoting – A Quest for New Ideas” and I was hoping to get other Quixote fans to provide their feedback on my use of his name. You see, I would like to do a little positive PR for the errant knight.

My blog’s address is: http://quixoting.typepad.com

I realize this is an old post, but i was hoping you’d still be looking . . .

I just started reading Don Quixote, though I’ve wanted to for a long time, and I found these notes helpful in figuring out what’s going on in the story. It’s ironic, and almost funny reading about the whimsical, make-believe adventures of a grown man.

hi i just

Sounds interesting here. Planning to have it one as I really like the reviews.

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but,

I’d like to send you an email. I’ve got some recommendations for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great website and I look forward to seeing it develop over time.

Right now it appears like Expression Engine is the

preferred blogging platform out there right now.

(from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?